Rethinking Mental Health Interventions: How Crowd-Powered Therapy Can Help Everyone Help Everyone

By C. Estelle Smith on

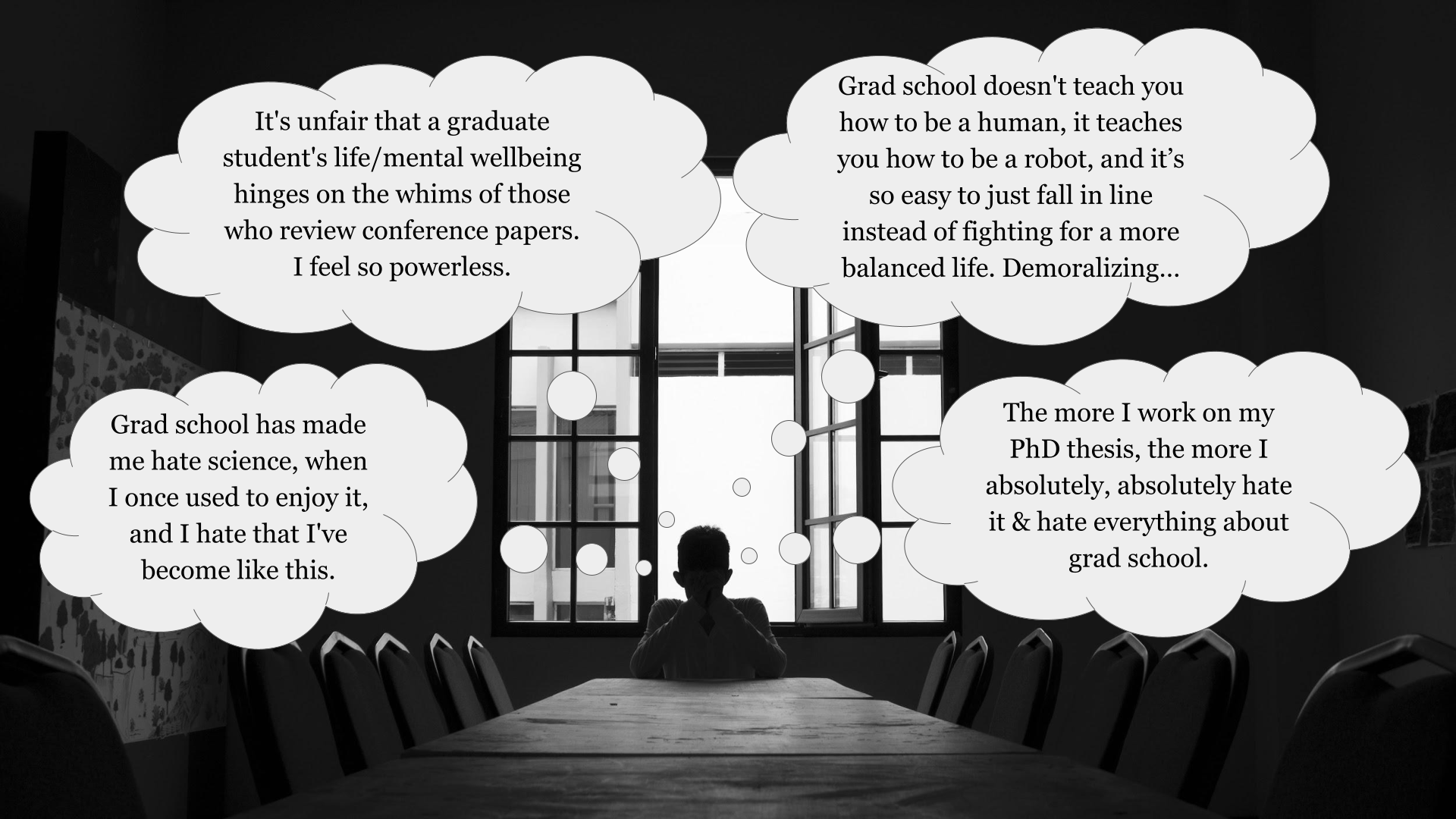

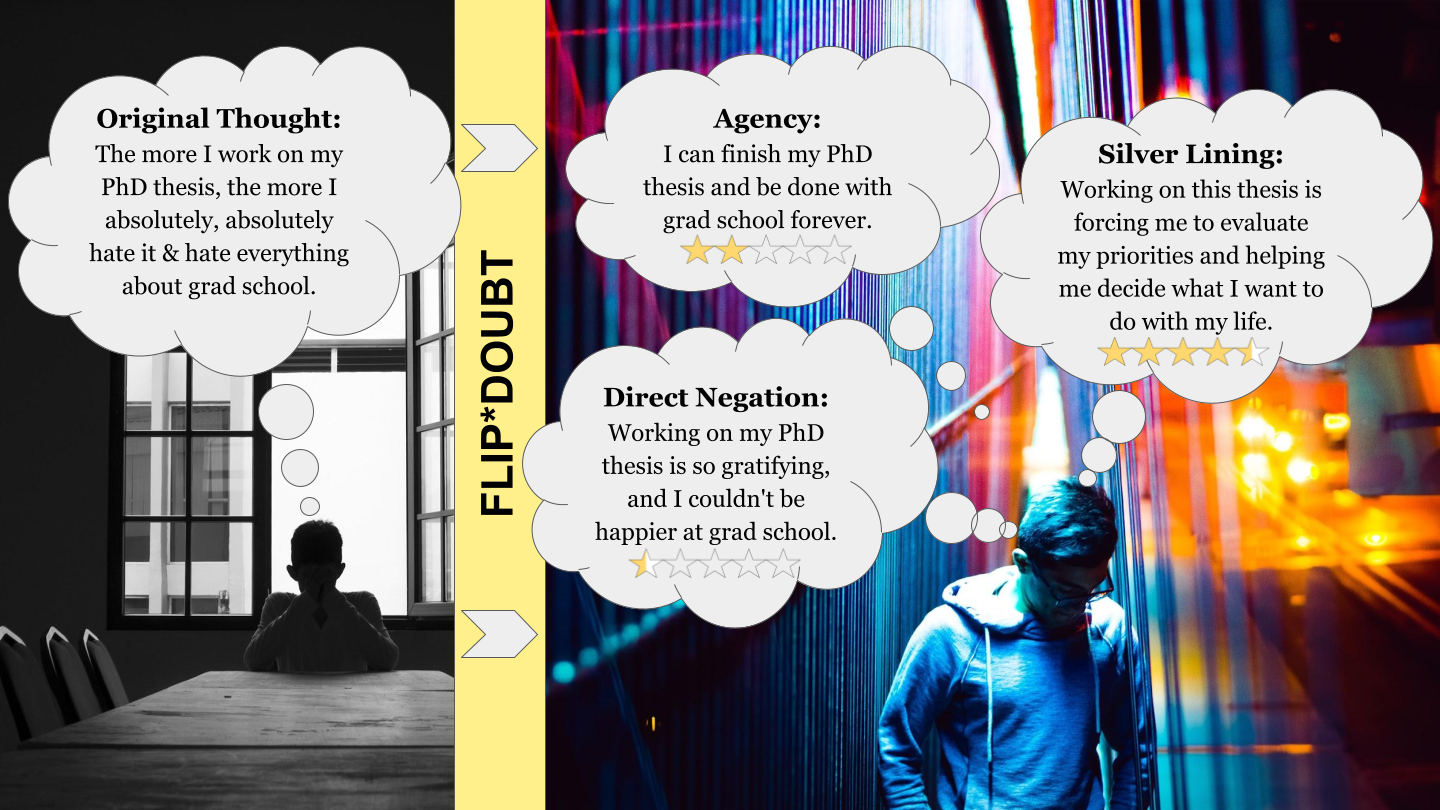

We all have dark thoughts sometimes. And if you’ve ever been a graduate student, perhaps thoughts like the following feel familiar:

The thoughts in this image are real data points collected during deployment of a prototype called Flip*Doubt, an app in which negative thoughts are entered and then sent to three random crowd workers to be “positively reframed” and sent back to the user. (The full paper title is “Effective Strategies for Crowd-Powered Cognitive Reappraisal Systems: A Field Deployment of the Flip*Doubt Web Application for Mental Health” and you can read it here.)

Rates of mental illness continue to rise every year. Yet there are nowhere near enough trained mental health professionals available to meet the need–and Covid-19 has only worsened the state of affairs. In short–we urgently need to rethink how we design mental health interventions so that they are more scalable, accessible, affordable, effective, and safe.

So, how can technology create new ways to expand models of delivery for clinically validated therapeutic techniques? In Flip*Doubt, we focus on “cognitive reappraisal”–a well-researched technique for changing one’s thoughts about a situation in order to improve emotional wellbeing. This skill is often taught by trained therapists (e.g., in Cognitive and Dialectical Behavioral Therapy), and it has been shown to be highly effective at reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression. The problem is, it’s really hard to learn, and even harder to apply in one’s own mind on an ongoing basis.

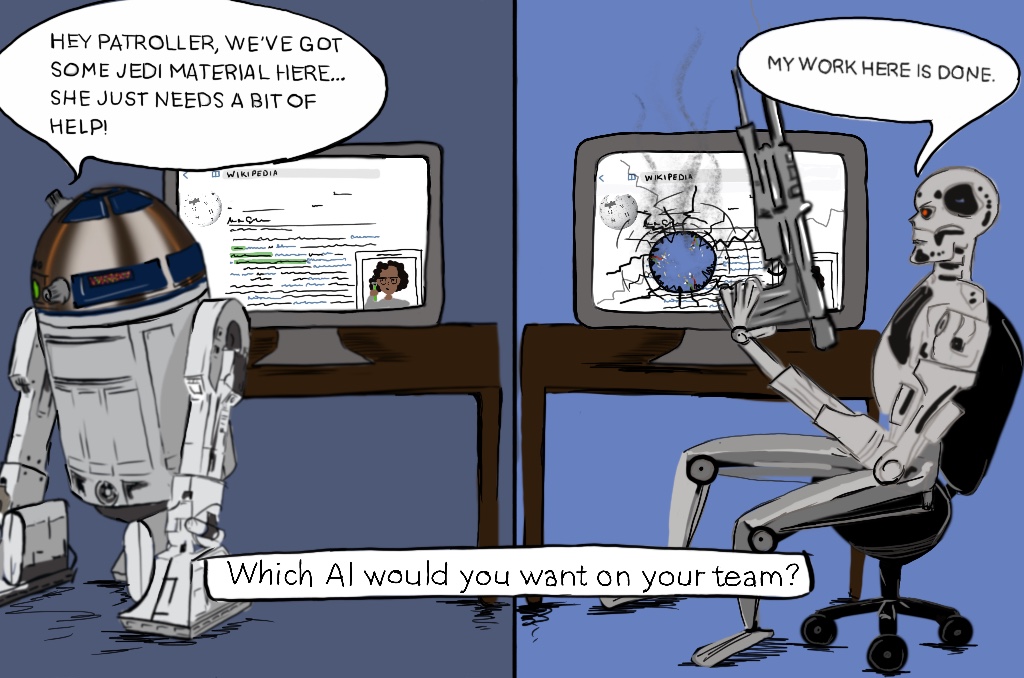

We envision that people could learn the skill through practice by reframing thoughts for each other–since research shows that it’s easier to learn by objectively sizing up others’ thoughts, rather than immediately trying to challenge your own entrenched ways of thinking. Thus, Flip*Doubt relies on crowd workers to create reframes, and the major driving questions of our study were: What makes reframes good or bad? And how can we design systems that effectively help people to nail the skill?

Our deployment yielded some fascinating results about how people use cognitive reappraisal systems in the wild, the types of negative thought patterns that weigh grad students down, and what types of strategies are most effective at flipping dark thoughts. For instance, the example below shows how a participant rated three reframes from Flip*Doubt:

Represented here are three different reappraisal tactics for transforming the original thought that we identified through our data analysis. “Direct negation” isn’t effective at all–it’s just invalidating and frustrating for someone to suggest the opposite of what you’re struggling with. “Agency” rings more true–yet can feel a bit simplistic. “Silver Lining” wins the gold for this thought–it provides fresh perspective by emphasizing an important positive that wouldn’t be possible without all the struggle. Our paper provides additional analyses, culminating in six hypotheses for what makes an effective reframe.

Our work suggests several important design implications. First, systems should consider prompting for structured reflection rather than prompting for negative thoughts. People aren’t always thinking negatively, and only allowing negative thoughts for input can reinforce those thoughts, or drive people away. Second, systems should consider tailoring user experiences to focus on a few core issues, since the best gains may come if meaningful progress can be made to address vicious and repetitive thoughts, rather than any old negative thought. Finally, crowd-powered systems can be safer and more effective if we design AI/ML-based mechanisms to help peers shape their responses through effective reappraisal strategies and behaviors–there’s a lot more on this in the paper, so we hope you’ll read about it there.

We’re honored that this paper won an Honorable Mention at #CSCW2021, since the world truly needs new interventions like Flip*Doubt to help us all to help each other. You can find the full paper at https://z.umn.edu/flipdoubt or watch the virtual presentation on YouTube.

Thanks for reading, and we hope to discuss this work with you at CSCW and beyond.