Couchsurfing and Airbnb are websites that connect people with an extra guest room or couch with random strangers on the Internet who are looking for a place to stay. Although Couchsurfing predates Airbnb by about five years, the two sites are designed to help people do the same basic thing and they work in extremely similar ways. They differ, however, in one crucial respect. On Couchsurfing, the exchange of money in return for hosting is explicitly banned. In other words, couchsurfing only supports the social exchange of hospitality. On Airbnb, users must use money: the website is a market on which people can buy and sell hospitality.

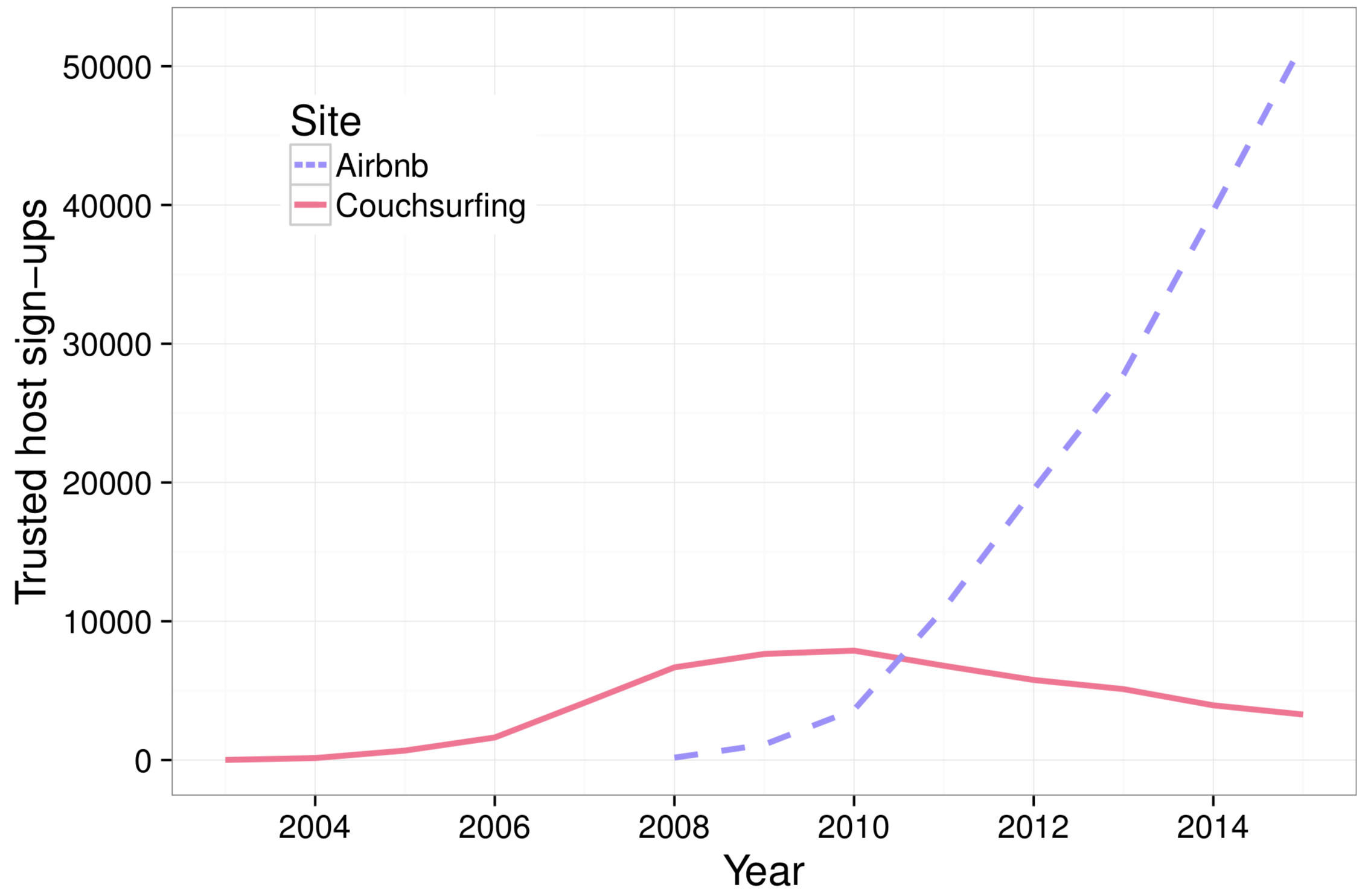

The figure above compares the number of people with at least some trust or verification on both Couchsurfing and Airbnb based on when each user signed up. The picture, as Mako Hill has argued elsewhere, reflects a broader pattern that has occurred on the web over the last 15 years. Increasingly, social-based systems of production and exchange, many like Couchsurfing created during the first decade of the Internet boom, are being supplanted and eclipsed by similar market-based players like Airbnb.

In a paper led by Max Klein that was recently published and will be presented at the ACM Conference on Computer-supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (CSCW) which will be held in Jersey City in early November 2018, we sought to provide a window into what this change means and what might be at stake. At the core of our research were a set of interviews we conducted with “dual-users” (i.e. users experienced on both Couchsurfing and Airbnb). Analyses of these interviews pointed to three major differences, which we explored quantitatively from public data on the two sites.

First, we found that users felt that hosting on Airbnb appears to require higher quality services than Couchsurfing. For example, we found that people who at some point only hosted on Couchsurfing often said that they did not host on Airbnb because they felt that their homes weren’t of sufficient quality. One participant explained that:

“I always wanted to host on Airbnb but I didn’t actually have a bedroom that I felt would be sufficient for guests who are paying for it.”

An another interviewee said:

“If I were to be paying for it, I’d expect a nice stay. This is why I never Airbnb-hosted before, because recently I couldn’t enable that [kind of hosting].”

We conducted a quantitative analysis of rates of Airbnb and Couchsurfing in different cities in the United States and found that median home prices are positively related to number of per capita Airbnb hosts and a negatively related to the number of Couchsurfing hosts. Our exploratory models predicted that for each $100,000 increase in median house price in a city, there will be about 43.4 more Airbnb hosts per 100,000 citizens, and 3.8 fewer hosts on Couchsurfing.

A second major theme we identified was that, while Couchsurfing emphasizes people, Airbnb places more emphasis on places. One of our participants explained:

“People who go on Airbnb, they are looking for a specific goal, a specific service, expecting the place is going to be clean […] the water isn’t leaking from the sink. I know people who do Couchsurfing even though they could definitely afford to use Airbnb every time they travel, because they want that human experience.”

In a follow-up quantitative analysis we conducted of the profile text from hosts on the two websites with a commonly-used system for text analysis called LIWC, we found that, compared to Couchsurfing, a lower proportion of words in Airbnb profiles were classified as being about people while a larger proportion of words were classified as being about places.

Finally, our research suggested that although hosts are the powerful parties in exchange on Couchsurfing, social power shifts from hosts to guests on Airbnb. Reflecting a much broader theme in our interviews, one of our participants expressed this concisely, saying:

“On Airbnb the host is trying to attract the guest, whereas on Couchsurfing, it works the other way round. It’s the guest that has to make an effort for the host to accept them.”

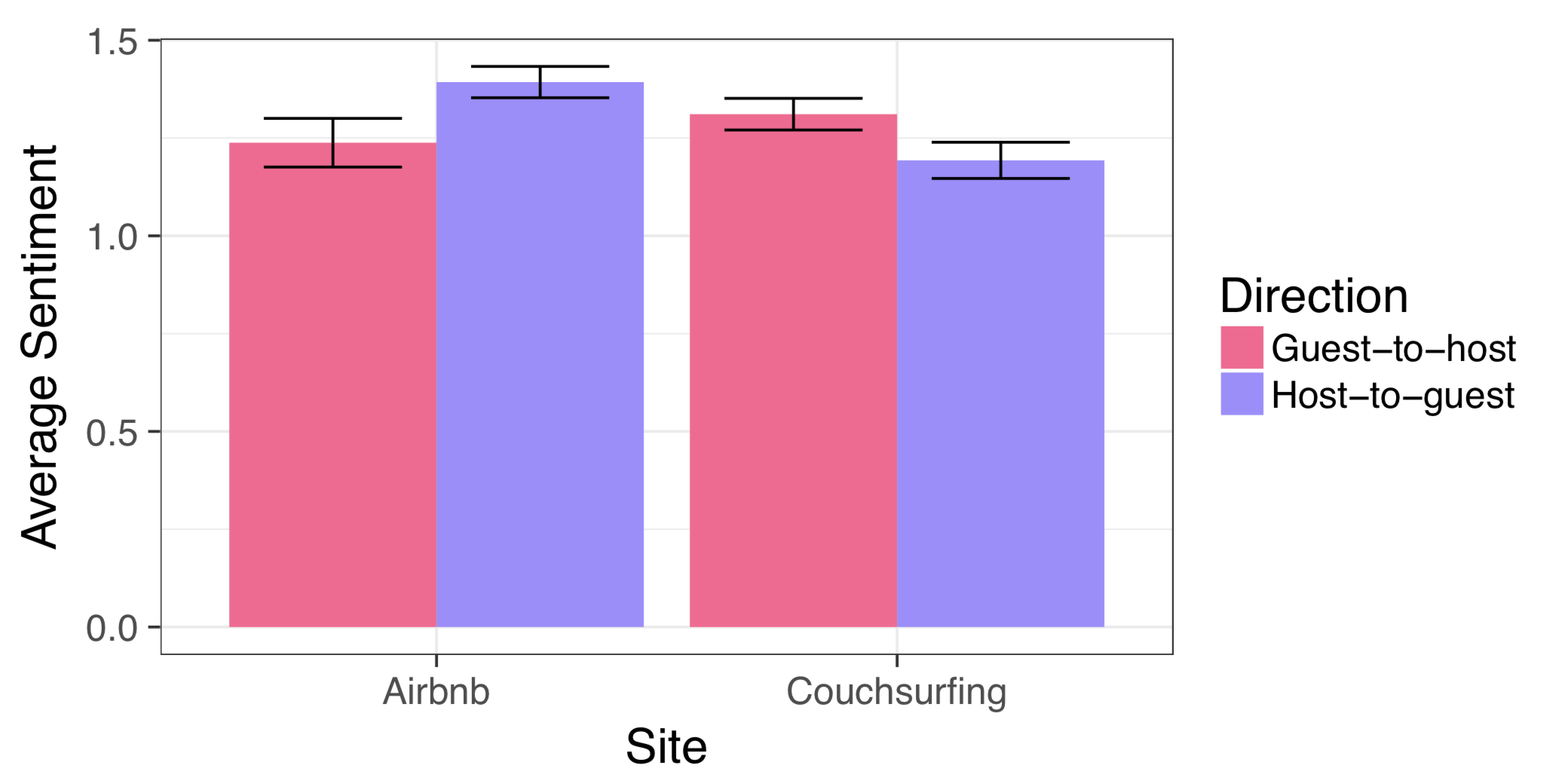

Previous research on Airbnb has shown that guests tend to give their hosts lower ratings than vice versa. Sociologists have suggested that this asymmetry in ratings will tend to reflect the direction of underlying social power balances.

We both replicated this finding from previous work and found that, as suggested in our interviews, the relationship is reversed on Couchsurfing. As shown in the figure above, we found Airbnb guests will typically give a less positive review to their host than vice-versa while in Couchsurfing guests will typically a more positive review to the host.

As Internet-based hospitality shifts from social systems to the market, we hope that our paper can point to some of what is changing and some of what is lost. For example, our first result suggests that less wealthy participants may be cut out by market-based platforms. Our second theme suggests a shift toward less human-focused modes of interaction brought on by increased “marketization.” We see the third theme as providing somewhat of a silver-lining in that shifting power toward guests was seen by some of our participants as a positive change in terms of safety and trust in that guests. Travelers in unfamiliar places often are often vulnerable and shifting power toward guests can be helpful.

Although our study is only of Couchsurfing and Airbnb, we believe that the shift away from social exchange and toward markets has broad implications across the sharing economy. We end our paper by speculating a little about the generalizability of our results. Mako Hill has recently spoken at much more length about the underlying dynamics in his his recent LibrePlanet keynote address.

More details are available in our paper which we have made available as a preprint on our website. The final version is behind a paywall in the ACM digital library.

This blog post, and paper that it describes, is a collaborative project by Maximilian Klein, Jinhao Zhao, Jiajun Ni, Isaac Johnson, Benjamin Mako Hill, and Haiyi Zhu. Support came from GroupLens Research at the University of Minnesota and the Department of Communication at the University of Washington.

Version of this blog post were reposted on several of our personal and institutional websites.