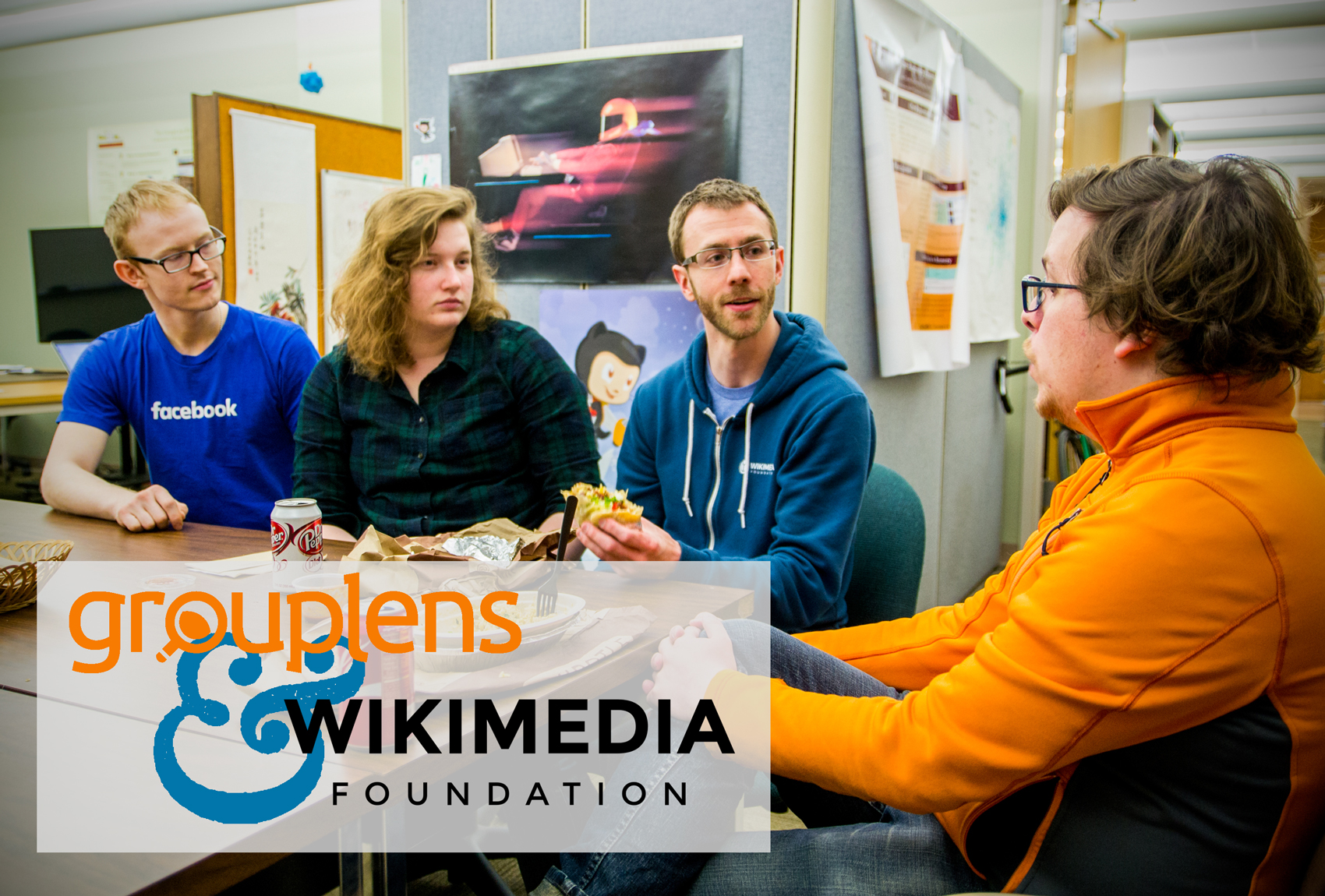

Aaron Halfaker peels back the gleaming foil of an overloaded burrito. Surrounded by doctoral candidates at the GroupLens lunch table, he chomps into his eagerly anticipated rice and beans, taking breaks to shoot the breeze or riff on research ideas. After earning his Ph.D. in 2013, Halfaker scored a full-time research job at the Wikimedia Foundation (WMF). Yet every Thursday, he returns to hang out with us on the University of Minnesota campus. This is certainly an unusual arrangement…what keeps him coming back?

In today’s info-hungry digiverse, Wikipedia feels like that lunch spot on the corner you can’t live without: it’s reliable, easy to take for granted, and difficult to imagine not being there for you. But unlike your favorite foil-wrapped ration, the entire menu of user-generated articles on Wikipedia is deliciously free — or at least it might seem that way to most visitors. In fact, maintaining the site’s behind-the-pages community and high quality content is a massive undertaking.

On top of hundreds of millions of human-hours donated by hundreds of thousands of volunteer editors [1], about 300 full-time WMF employees and a tight-knit community of several dozen more academic researchers pour their intellectual efforts into understanding or improving the platform. Historically, however, a non-trivial barrier stunted Wikipedia’s progress: WMF employees and academic researchers didn’t actually talk to each other.

“Researchers at the Palo Alto Research Center first noticed in 2009 that Wikipedia was in decline,” says Halfaker, by way of example. “But the Wikimedia Foundation noticed that same trend in 2011 and did an independent analysis. That took a huge amount of time.” Could such a seemingly simple yet practically intractable problem be solved over lunch?

Research on Wikipedia: An Open Conversation

Spanning the gap between industry and academia is tricky due to apparently conflicting incentive structures. With some notable exceptions, commercial organizations often guard trade secrets to protect profits and shareholders. Academics, on the other hand, create impact and advance their careers by disseminating ideas as broadly as possible — usually after results have been published in peer-reviewed venues.

By contrast, WMF occupies a unique industrial niche as a non-profit that depends on openness at every level. Excluding YouTube, Wikipedia operates at the same scale as Google with ~600 million unique readers per month. Unlike Google, which employs hundreds of researchers whose work is likely to be published only under some form of profit motive, the WMF expects its four — yes, exactly four — researchers to release all of their work under an open license.

“Peer review happens after the fact in wiki contexts,” says Halfaker. In fact, WMF researchers publish every aspect of their work as it is generated, including work logs, public conversations about those logs, code, and data. The resultant research reports are political documents – that is, Wikipedians who have invested substantial intellectual capital and time usually have strong opinions about what happens to Wikipedia.

“Anyone can see my original motivations, the mistakes I make, and why I made certain decisions,” says Halfaker. “I have a long history of openness that undercuts people who try to undermine the report. That openness has helped me build trust around research results — not trust in me, but trust that I followed a good process.”

Yet Halfaker’s openness extends beyond even WMF’s core requirements. While WMF is headquartered in San Francisco, Halfaker stayed in the Twin Cities as a remote full-time employee after earning his Ph.D. His job title at WMF is Principal Research Scientist. The real kicker, though, is that he also a job title with the Computer Science Department at the University of Minnesota as a Senior Scientist, and GroupLens has remained committed to Halfaker’s research, providing him with ongoing space and resources in lab. He still feels like he’s part of the team…because he actually is. He attends our meetings in-person and shares his expertise. We collaborate on interesting projects. And because we’re all friends, he even joins us for lunch.

Breaking Ice with Industry

Halfaker began edging into his unique position with the publication of his first paper in 2009 under the advisorship of John Riedl, a founding faculty member of GroupLens with a major research focus on Wikipedia. Halfaker found that being new on Wikipedia was the single greatest predictor of having edits reverted.[2]

Following a WMF outreach program in 2011, Halfaker landed a summer internship with WMF to study population dynamics on Wikipedia. He found that the phenomenon of newcomer reversion causes many would-be editors to have negative introductory experiences and abandon editing activities, possibly contributing to Wikipedia’s decline.[3]

After his summer internship, Halfaker returned to GroupLens to dig deeper into this problem for his thesis. Instead of keeping WMF out of the loop, however, he kept the conversation and collaborative process open, making for a seamless transition into his WMF job after graduation. Now, Halfaker’s work attempts to optimize the tradeoff between strict quality control and a good newcomer experience.

Another of Halfaker’s lines of inquiry explores vandalism on Wikipedia. Currently, a pipelined ecosystem of bots and humans work together to rapidly revert vandalism in an average of 15 seconds. Halfaker showed that when Cluebot (a crucial vandalism-battling bot) goes down, the reversion process takes twice as long.[4] Today, he continues to study and implement vandalism-reducing measures on Wikipedia. (Check out this nifty AI tool and this Wired article.)

Halfaker’s prior academic research now directly impacts his professional agenda. However, the foundations for his unique line-straddling position had actually been laid in over a decade of GroupLens research.

GroupLens Papers & Wikimedia Policy

Within every organization, funding decisions are always critical conversations. Having evidence (such as academic research) to support resource allocation is pivotal. For instance, a GroupLens paper authored by Reid Priedhorsky, et al. (2007) showed that only one tenth of one percent of editors on Wikipedia contribute about half of its content.[5] At WMF, this paper helped socialize the idea that, in addition to thinking about the massive group of all editors, it is equally important to design custom features for the comparatively tiny group of super users.

Another GroupLens paper authored by Tony Lam, et al. (2011) showed not only that gender bias exists, but also that this bias affects quality and content coverage on Wikipedia.[6] As a result of this research, WMF now seeks to highlight gaps in its content coverage and invest in outreach to fill them.

Halfaker’s more recent work is also heavily cited internally. For example, Cluebot is built on top of Wikimedia Labs, a cloud computing infrastructure that connects volunteers with Wikimedia operations and software development. Halfaker’s vandalism paper [4] helped to justify maintaining Labs. “The Wikimedia Foundation has a strong internal culture of citing sources,” says Chase Pettet, Lead Operations Engineer at Wikimedia Cloud Services. “It has been invaluable to have concrete analysis for understanding on-wiki community impact when making the argument internally for the allocation of resources.”

All of the above examples have had important consequences for the Wikipedia community…eventually. However, it took some time for these results to circulate and impact the organization. One of Halfaker’s emergent roles at the organization has been to explicitly connect academia with WMF’s interests, and to facilitate conversations that unite both in a mutually beneficial relationship.

Incentive Alignment to Expedite Impact

When Halfaker comes to GroupLens on Thursdays, he doesn’t simply catch up on the latest academic research. Rather, his position is the ongoing manifestation of a committed relationship between GroupLens and WMF. He is our dedicated collaborator, a conduit for two-way communication, and even more importantly, a translator. That is, faculty, Ph.D. students, and WMF employees often have similar or complementary requirements and objectives…but they communicate those goals quite differently.

“I make a lot of introductions with decision-makers at the Wikimedia Foundation and I communicate their concerns to GroupLensers,” says Halfaker. “Researchers and WMF staff are really worried about similar things – I just make connections and help align language so people know how to talk to each other.”

The fruits of this alignment clearly benefit GroupLens researchers by providing access to internal WMF data and resources. According to Dario Taraborelli, Head of the Research Department, this unique situation also pays off for WMF. “Over the years, GroupLens has made enormous contributions to our understanding of Wikipedia and peer production in general,” says Taraborelli. “The ability for the Wikimedia Foundation to tap talented collaborators and to align our internal research agenda, and the problems the Wikimedia movement cares about, with research priorities at GroupLens, has produced impactful work. Aaron’s role in keeping the two organizations connected has been key to the success of this collaboration.”

Halfaker’s presence at the lab represents both an open invitation and an ongoing source of support for students and faculty alike. “Aaron has collaborated with and mentored multiple GroupLens students in the past few years, both as interns at the Wikimedia Foundation and in informal collaborations,” says Loren Terveen, distinguished McKnight Professor and longstanding GroupLens Faculty member. “These projects have led to well-received research papers, valuable practical results for Wikipedia, and rich growth experiences for the students.” Halfaker currently works with Ph.D. candidates Andrew Hall and Jacob Thebault-Spieker, and GroupLens alumni, Morten Warncke-Wang and Shilad Sen.

Other online communities like Reddit, Wikia, and Wikihow, have occasionally opened themselves up to collaboration, though such efforts have proven difficult to sustain. In the future, new online tools and platforms could viably enable direct communication between academia and industry.

Before that happens, however, Halfaker’s unique position between industry and the ivory tower is increasing the rate at which GroupLens research gets picked up by WMF and helping to route results directly to relevant product teams. He helps academics with access to data, code, and internal expertise, while expanding WMF’s broader research capacity by helping to direct academic efforts.

With increased flexibility, openness, and commitment on both sides — plus a burrito or two? — bridging the gap is an appetizing opportunity space.

[Thanks to Joe Konstan and Loren Terveen for their comments on this blog post, and to Joe for the title. Please comment below or send me an email at smit3694@umn.edu to continue the conversation.]

References

[1] Geiger, R. S., & Halfaker, A. (2013, February). Using edit sessions to measure participation in Wikipedia. In Proceedings of the 2013 conference on Computer supported cooperative work (pp. 861-870). ACM.

[2] Halfaker, A., Kittur, A., & Riedl, J. (2011, October). Don’t bite the newbies: how reverts affect the quantity and quality of Wikipedia work. In Proceedings of the 7th international symposium on wikis and open collaboration (pp. 163-172). ACM.

[3] Halfaker, A., Geiger, R. S., Morgan, J. T., & Riedl, J. (2013). The rise and decline of an open collaboration system: How Wikipedia’s reaction to popularity is causing its decline. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(5), 664-688.

[4] Geiger, R. S., & Halfaker, A. (2013, August). When the levee breaks: without bots, what happens to Wikipedia’s quality control processes?. In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Open Collaboration (p. 6). ACM.

[5] Priedhorsky, R., Chen, J., Lam, S. T. K., Panciera, K., Terveen, L., & Riedl, J. (2007, November). Creating, destroying, and restoring value in Wikipedia. In Proceedings of the 2007 international ACM conference on Supporting group work (pp. 259-268). ACM.

[6] Lam, S. T. K., Uduwage, A., Dong, Z., Sen, S., Musicant, D. R., Terveen, L., & Riedl, J. (2011, October). WP: clubhouse?: an exploration of Wikipedia’s gender imbalance. In Proceedings of the 7th international symposium on Wikis and open collaboration (pp. 1-10). ACM.