[Cross-posted from Estelle’s Blog]

Mainstream media are most adults’ primary source of new information about science. Yet even when mainstream media outlets cover science (which they rarely do), the coverage contains errors approximately 20-30% of the time. Consequently, a hefty majority of Americans (over 70%!) lack adequate literacy to reason about scientific evidence as it relates to civic life. As scientists, how can we bridge the gap between the ivory tower and the general public?

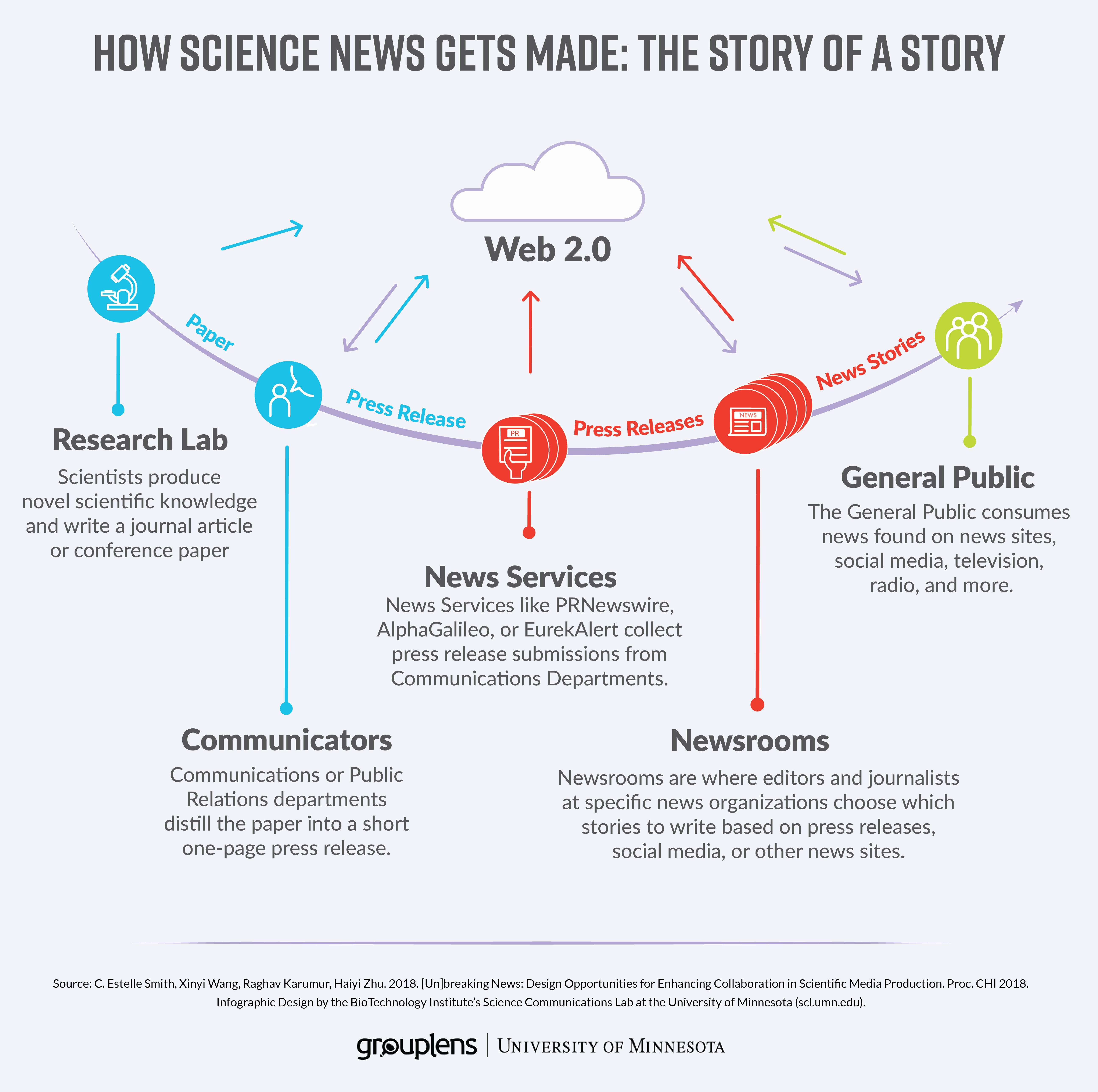

We interviewed researchers, journalists, and everyone in-between in order to understand how science news gets made, why it’s often challenging to produce, and what opportunities exist for new technological innovation. Check out the infographic above for a simplified visualization of the Media Production Pipeline (MPP), but make sure to read our forthcoming CHI paper entitled [Un]breaking News: Design Opportunities for Enhancing Collaboration in Scientific Media Production to get the whole story.

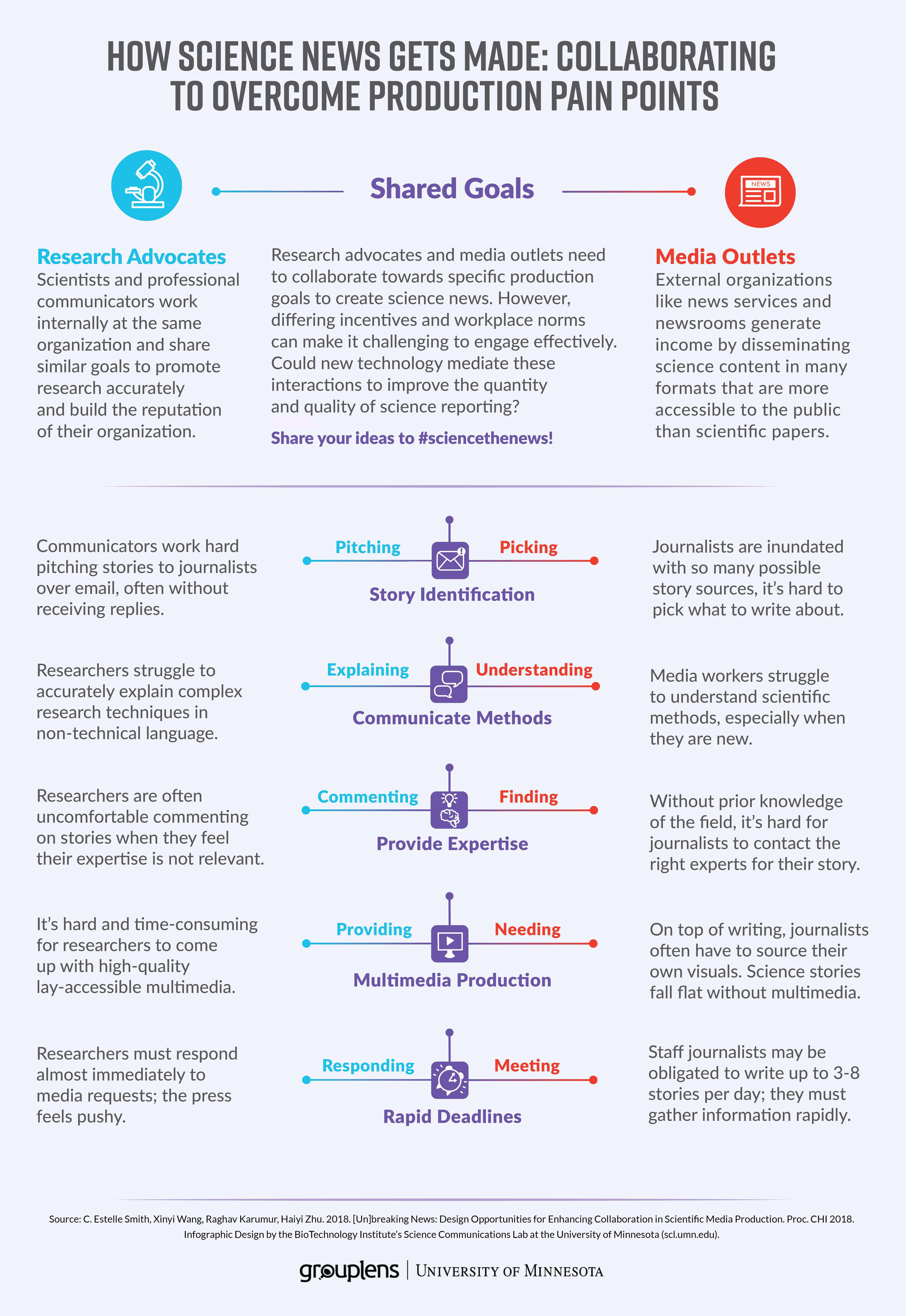

What’s critical to realize is that all of the diverse stakeholders involved in scientific media production have different skills, different incentives, and different definitions of success. The infographic below describes our primary results in more detail.

Scientists undergo extensive training to execute complex technical processes, and they might spend months or years creating a manuscript, yet the text, figures and images they produce aren’t usually comprehensible to the lay reader. Journalists have extensive training to craft effective and relatable narratives, yet they often have only hours or days to write a story, and they’re always juggling multiple stories at once. Plus, journalists need compelling visuals or multimedia to give their stories wings. Let’s just say, scientists aren’t artists, and they don’t generally have loads of catchy videos or photos lying around. These differences (and more) can result in awkward or failed interactions.

To top it all off, nobody truly knows exactly what stories the public should know. It takes a significant amount of effort for media professionals to sort through all the possible stories that could be written to find the right stories to write.

But what does all of this mean for technology designers?

We believe that future technology should make it easier for scientists to work with journalists, and for journalists to rapidly get the information they need to write accurate science stories. And no–that does not mean giving scientists the go-ahead to co-write or edit journalists’ work. Rather, it means supporting efficient interaction modalities that anticipate press engagement, generate materials ahead of time, and respect the perspectives of scientists and media professionals. We share our ideas in our paper, but we want to hear from you! Join the conversation with #sciencethenews.

…And then roll out of bed, grab a coffee, and come see the paper talk bright and early on Wednesday morning at CHI 2018 in Montreal, Canada! I’ll be presenting our work, which was awarded an Honorable Mention, on Wednesday, April 25, 2018 at 9am in Room 517D in the paper session: Curation & Collection. Mark your calendar.

As funding for scientific research dwindles, and powerful political and corporate interests continue to block and decry scientific progress, it has never been more important for scientists and journalists to work together. Our work lays down some groundwork; now it’s up to the scientific community to build new technologies and new attitudes towards public engagement.